🌟 Introducing the Baltic Refugee Support Hub! 🌍🤝

🌟 Introducing the Baltic Refugee Support Hub! 🌍🤝

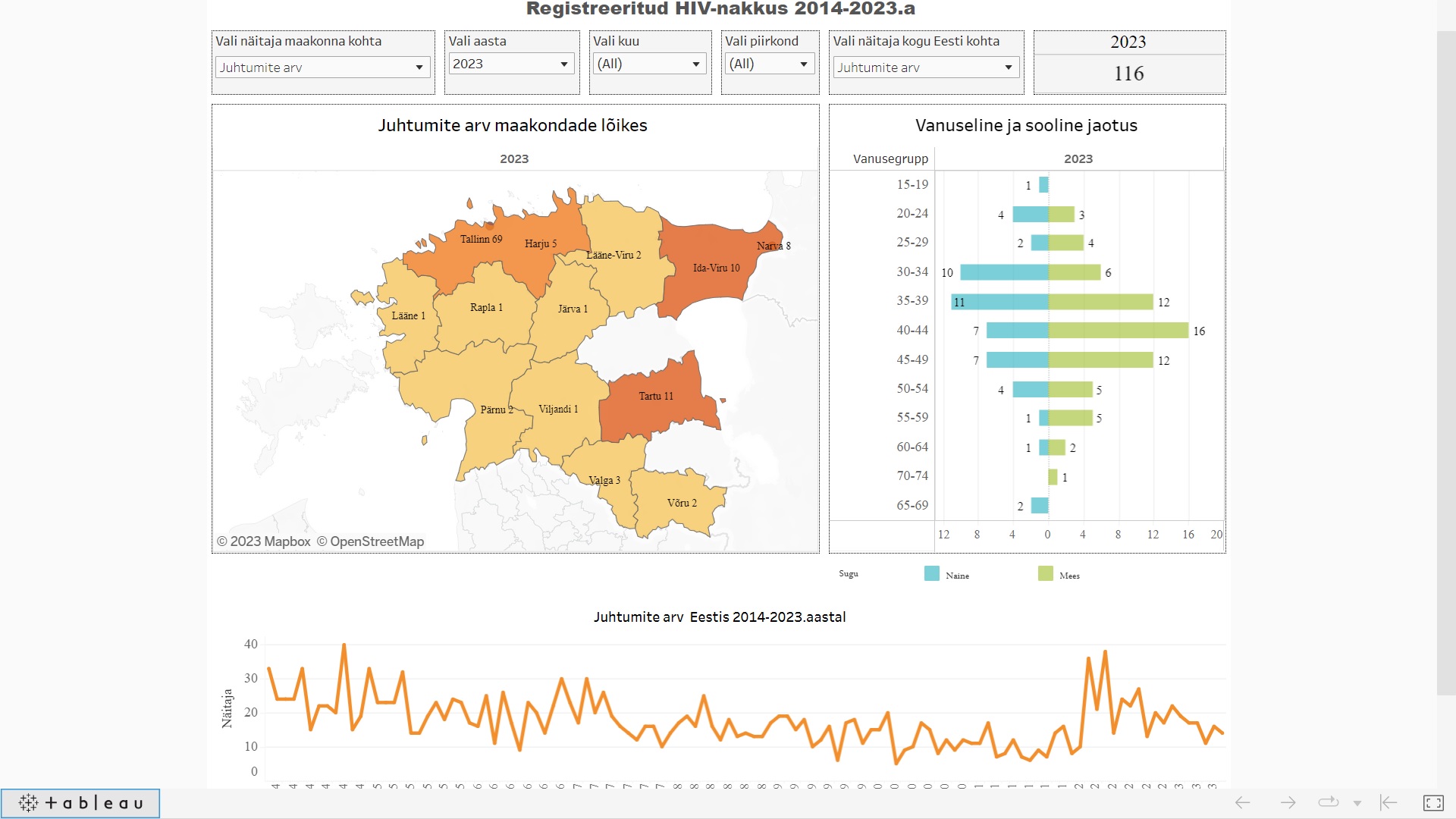

In the wake of russian aggression and invasion of Ukraine in 2022, a wave of refugees found their way to the shores of Europe, seeking safety and solace. The numbers were staggering – over 8 million refugees across Europe, with more than 500,000 finding refuge in the Baltic and Nordic regions, of which 1/3 were innocent children, and number of key populations representatives from Ukraine.

Amidst this challenge, a beacon of hope emerged – the Baltic Refugee Support Hub, brought to life by the tireless efforts of the NGO Estonian Network of People living with HIV. Operating from June 2023 to October 2024, this project aims to extend a helping hand to those in need and reshape their lives.

🤝 Partnership for Progress

Working shoulder to shoulder with AGIHAS in Latvia, Positiiviset ry and HivFinland in Finland, EHPV in Estonia, and planning to expand to Lithuania Norway, the Baltic Hub seeks to unite hearts and resources across borders. A powerful memorandum of understanding will be signed, setting the stage for a collective mission.

🏠 The Baltic Hub – supporting Ukrainian refugees

The Baltic Hub is more than a project – it’s a lifeline for those who’ve endured the hardships of war. It provides a central point of coordination for services spanning psycho-social, medical, socio-economic, legal, and informational realms. This refuge of support is open to Ukrainian refugees living with HIV, the LGBT+ community, families impacted by HIV, children, and other key groups.

🌐 A Compassionate Connection

Within the frames of activities we`re proud to announce that the multilingual website will be launched, designed to guide refugees in their journey toward better lives. This online portal, will be available in 7 languages, arming refugees with the information they need, directing them to the services available in their new countries. It’s a digital bridge to brighter tomorrows for those in need.

💬 Spreading the Message

The Baltic Hub isn’t just about infrastructure – it’s about ensuring every person who needs help can find it. Through a strategic communication campaign, we will be reaching out to Ukrainian AIDS centers, friendly family doctors, and NGOs working with key groups. Together, we will be promoting the website as a beacon of assistance, a lifeline for those seeking refuge in Baltic Countries.

🌟 Shaping a Sustainable Future

The journey doesn’t end with this project. A grand online conference will convene at the project’s close, sharing lessons learned and casting a vision for the Baltic Hub beyond these initial steps. It’s about building bridges that stand the test of time, offering hope to those in search of a brighter future.

🌍 Impact Beyond Borders

Join us in making a real impact. Together, we’re fostering increased welfare for war refugees – from HIV-positive individuals and their families to children and the LGBT+ community. With the Baltic Hub, an international informational service provision mechanism, we’re shaping a future where compassion knows no bounds.

🤝 Partners:

The Baltic Refugees Support HUB project is supported by Nordic Council of Ministers.

In country Partners are: AGIHAS, Latvia | Positiiviset ry, HivFinland, Finland | EHPV, Estonia | Demetra, Lithuania and others

Let’s change lives, one step at a time.

#BalticRefugeeSupportHub #StrongerTogether